Clarinet Shadows

Featuring clarinetists Jerome Simas and Jeff Anderle, this haunting program pairs Brahms’ autumnal clarinet quintet with Jonathan Russell’s On Sorrow and a new miniature from Josiah Catalan.

Inspired by and quoting Tomas Luis de Victoria’s O Vos Omnes, Russell’s quintet explores mortality, consolation, and common humanity across the centuries, finding common themes with one of Brahms’ final and most profound chamber works.

Program includes:

Josiah Catalan (Pathways Mentor) - micromechanisms 4, 5, & 6 (WORLD PREMIERE)

Jonathan Russell - On Sorrow

Johannes Brahms - Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115

Artists

Anna Presler, violin

Liana Berube, violin (guest artist)

Phyllis Kamrin, viola

Leighton Fong, cello

Jerome Simas, clarinet

Jeff Anderle, clarinet (guest artist)

Meet the composers

-

Jonathan Russell

On Sorrow

Notes by the composer

On March 31st, 2017, my 37-year-old wife was diagnosed with what turned out to be Stage III Breast Cancer, and our life was turned upside down. We made the decision to leave London, where we had lived for the past four years, and move in with her parents in Weymouth, Massachusetts for the duration of her treatment. All told, it was about a year from initial diagnosis to my wife starting to feel like herself again. For now, she is considered “cancer-free”, but the very real possibility of a more serious recurrence will always haunt us. Fear, worry, anxiety and exhaustion – not “sorrow” – were the sensations that dominated the year. But as I contemplated the very real possibility of losing my life partner much sooner than anticipated, I became far more conscious of sorrow’s inevitability in all of our lives, of the weight of loss that everyone ultimately carries. For no matter how lucky a life we live, the simple fact remains that the longer we are here the more loss we will experience.The piece is in five continuous movements that flow together without pause:I. Prelude – LossII. WithdrawalIII. RageIV. Consolation (O Vos Omnes)V. Renewal – PostludeThe piece opens with wispy string chords in a stuttering rhythm, with the bass clarinet floating above, evoking the eternal, endless river of time, the neutral backdrop to the cares and concerns of living. This figure also takes on a quality of “fate,” appearing again, suddenly loud and forceful, at the climaxes of the first, third, and fifth movements. After a few minutes of this material, the main “sorrow” theme of the piece enters: a circular, chromatic figure in five. This material begins slowly and lugubriously, but gradually starts to become more flowing and buoyant. Before it can go too far in this direction, however, it is interrupted by a hammering version of the “fate” motive. This is followed by two intense statements of the “sorrow” theme, and then a high, wispy version that melts into the second movement.Movement 2 (“Withdrawal”) evokes the sense of turning inward and separating from the world that is often our initial way of coping with the shock of a calamitous event. The bass clarinet plays fragmentary melodies over quiet, repeating chords in the strings that begin high and ethereal, and gradually drift down and down and down. At the end, there is a low, subdued statement of the “sorrow” theme – which then triggers the third movement’s sudden outburst. Movement 3 (“Rage”) is aggressive, dissonant, and driving. There are several new themes, and the “sorrow” theme is also sucked into the vortex. Its narrow chromatic pitches are played in close canon to create buzzing, insect-like swirls of dissonance. The music churns to a climax, and the bass clarinet is left alone on one of its lowest pitches. The strings hammer out the “fate” motive repeatedly as the bass clarinet ascends four octaves, almost its entire range, and is left hanging alone on a searing high note. When the bass clarinet stops, a lone, gentle sustained cello note emerges, leading into the fourth movement, “Consolation (O Vos Omnes).” This movement consists entirely of fragments from Tomás Luis de Victoria’s choral work “O Vos Omnes,” composed in the vicinity of 1572. It is a beautiful, contemplative work, setting a text from Lamentations 1:12, which translates as: “O you that pass by, behold, and see: if there be any sorrow like my sorrow. Pay attention, all people, and see my sorrow: if there be any sorrow like my sorrow.” I knew early on that Victoria’s composition would inform my own, both because it is such a potent musical evocation of sorrow, and, more personally, because it has itself been a source of consolation for me in difficult times. As my piece developed, it became clear to me that directly quoting Victoria’s work would be the most compelling way to provide the “consolation” music I was seeking. It is deeply inspiring and humbling to me that a piece of music composed 450 years ago can still speak to us so directly and immediately today. It is a testament to the power of music itself to console, as well as to the power of spirituality and our common humanity, even across many generations and centuries.As the fourth movement ends, Victoria’s final cadence morphs into a statement of the “sorrow” theme. The bass clarinet begins movement 5 (“Renewal”) with tentative fragments of this theme, which are then picked up by the first violin. The other instruments gradually join in, with the theme gathering in strength and confidence, finally culminating in a vigorous tango, a swirling, churning dance of life. Sorrow is not denied or defeated, but instead becomes the very basis for renewal and hope. As in the first movement, the dance is cut short by a hammering return of the “fate” motive. This time, however, the harmonies build and finally resolve to a triumphant D major chord. The chord melts away and we are left once again with three iterations of the slow, contemplative version of the “sorrow” theme, rising higher each time, finally leaving the bass clarinet suspended gently in the air. The quiet, wispy version of the opening “fate” motive enters in the strings, and the piece ends as it began, with the bass clarinet suspended over a gently pulsating ocean of time. The piece, like sorrow itself, has fractal and cyclical qualities. The process it evokes can happen on many time scales, successively or simultaneously. The sequence of emotions could be happening in real time over the course of the 30-minute work; or it could happen over the course of an instant, a year, a lifetime. The ending of the piece could lead directly back to the beginning: even as we overcome one sorrow, the next one may be just on the horizon, or already underway. And even the sorrows we think we have overcome will continue to be with us, carrying us again through their gauntlet of emotions when we least expect it.As long as humans are mortal, sorrow will be a central part of existence. And as long as humans are human, we will seek out ways to process, console, heal, and renew. My hope is that this composition can be one small contribution to that endless and eternal human project.Josiah Catalan

micromechanisms

Notes by the composer

micromechanisms is an ongoing series of short compositions that I started in 2018 and are often inspired by objects or events that form the basis of underlying musical mechanisms constructed throughout each piece. Numbers 4, 5, & 6 draw inspiration from things specific to California; No. 4 is inspired by the Feather River Fish Hatchery, No. 5 is on the Frozen Creeks of the Sierras, and No. 6 is based on mesmerizing and sinful Ghirardelli chocolate conches located in the original factory.Johannes Brahms

Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115

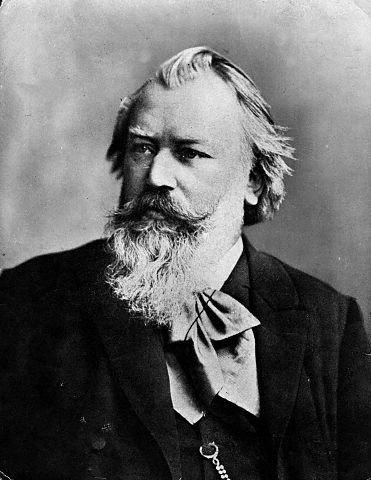

Notes by Emily ThomasJohannes Brahms (1833-1897) seemed to exist most naturally in a state of contradiction. He was a staunch admirer of tradition who at times composed music so saturated with feeling that the rigid bounds of classical forms were forced to bend to contain it; a deeply emotional person whose many loves found their only expression in his doting melodies and bold harmonic movements; a composer with a reputation that verged on mythical, whose mid-life pastimes included ruthlessly revising his symphonies and stamping out the memories of his own works. It is fitting that at the height of his career in composition Brahms resolved to retreat into retirement.

Taking much inspiration from classical and pre-classical composers, Brahms rose steadily to prominence throughout the nineteenth century, composing primarily within well-trodden musical forms and establishing himself as a master handler of counterpoint, rhythm, and meter. His music blurred the lines between Classical and Romantic, the conservative and the radical, the stoic and the impassioned: ambiguities that garnered incredibly varied reactions from his critics and fellow composers alike. Before he’d turned 50, his acclaim had reached prodigious proportions, eventually earning him a place in Hans von Bülow’s “The Three B’s” — a classification that placed him on the same level of artistry and legacy as Ludwig van Beethoven and Johann Sebastian Bach. It was only after the massively successful 1890 premiere of his String Quintet No. 2 in G Major, though, that Brahms at last believed he “had achieved enough” and that “[he] had before [him] a carefree old age and could enjoy it in peace.” Retirement from music would afford Brahms reprieve not only from the watchful eyes (and ears) of his contemporaries but also from his own highly self-critical nature. Brahms decided to settle into retirement, to live out the rest of his days in ease and leisure at his home in Vienna — a conviction that lasted all of four months.

It was the expert playing of clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld that inspired Brahms to abandon all notions of retirement. A regular performer in the courts of Duke George in Meiningen, Germany, Mühlfeld was known not only for his commanding musicianship but also for his liberal use of vibrato, on par with that of string musicians and unusual among clarinet players of the time. In March of 1891, Brahms attended Mühlfeld’s performance of Weber’s Clarinet Concerto No. 1. So taken was Brahms with the distinctive sound and virtuosity of Mühlfeld that he composed two works — one of which was his Clarinet Quintet (Op. 115) — specifically for Mühlfeld within months of his introduction to the clarinetist. By the end of the year, the piece had received its premiere at the very same courts in Meiningen with Mühlfeld as the clarinet soloist, and Brahms’s briefly fading career was reignited in full.

Like much of Brahms’s music, the Clarinet Quintet reveals the peculiar synergy that can arise when contradictory elements — simple and compound meters, for instance — occupy the same space in a musical work. A striking characteristic of the piece is the malleability of the thematic material: the music’s surprising suitability to both major and minor tonalities. In the first movement (Allegro), it is two dozen measures before the minor key is established with any sort of conviction, the preceding music vacillating with expert ambiguity between major and minor. This trend carries over into the second movement (Adagio), in which it becomes clear just why the clarinet had so enchanted Brahms in the adept hands of Mühlfeld, who doubtless revealed the instrument’s full palette of timbral colors and melodic abilities. Brahms takes full advantage of the instrument’s own aptitude for contradiction: At times, the character of the instrument so suddenly and completely inverts that it sounds as if a second clarinet has overtaken the first, its soaring voice springing back and forth between one of lingering sentimentality to one of dexterity often reserved for improvisation. The third and shortest movement (Andantino) opens with a theme in the major key and quickly transforms into a variation on that theme in the relative minor before concluding as it began. So continues Brahms’s major-minor interplay. This is followed by the fourth and final movement, (Con moto, “with movement”), which features a five-variation structure. The conclusion of this last movement is virtually identical to that of the first movement with the exception of the very last chord, the statement of which was marked piano in the first movement but returns in these final seconds in resounding forte before fading eventually back to piano. Even an apparently clear-cut transformation such as this one aligns with the nature of other musical “movements” throughout the piece, which tend to contradict themselves, “moving” but always seeming to return.

PRESS RELEASE - coming soon

>> VACCINATION & MASK POLICY

Proof of COVID-19 vaccination and masking are no longer required at these venues.

Image credit: Copyright Henry White, used by permission of Artist. Henry White is a landscape painter working in oils. These are some of his paintings of the oaks, hills and skies of our beautiful Bay Area and beyond. The banner image is a detail of Misty Morning.

Sunday, January 21, 2024, 4:00 PM

First Church of Christ Scientist

2619 Dwight Way

Berkeley, CA 94704

Monday, January 22, 2024, 7:30 PM

San Francisco Conservatory of Music

50 Oak Street

San Francisco, CA 94102