Sonic Luxury

Samuel Coleridge Taylor - Clarinet Quintet in F-sharp minor, Op. 10

Clara Schumann - Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op 20

Derek Bermel - Soul Garden

Esa-Pekka Salonen - Nachtlieder, for clarinet and piano

Enjoy the full spectrum of sonic luxury from Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s joyous Clarinet Quintet to Clara Schumann’s velvety piano variations to Esa-Pekka Salonen’s haunting duo, Nachtlieder. And violist Kurt Rohde shines in Derek Bermel's concerto for viola and string quintet, the "seductive, culture-crossing" Soul Garden. (Boston Globe)

VIRTUAL CONCERT:

Monday, June 7, 2021, 7:30 PM

This event is free to join, but we ask you to consider making a donation of $25, or whatever you’re able.

Artists

Anna Presler, violin

Phyllis Kamrin, violin

Kurt Rohde, viola

Matilda Hofman, viola

Leighton Fong, cello

Tanya Tomkins, cello

Eric Zivian, piano*

Jerome Simas, clarinet

*Eric Zivian’s performance is made possible by a generous grant from the Ross McKee Foundation

Program Notes

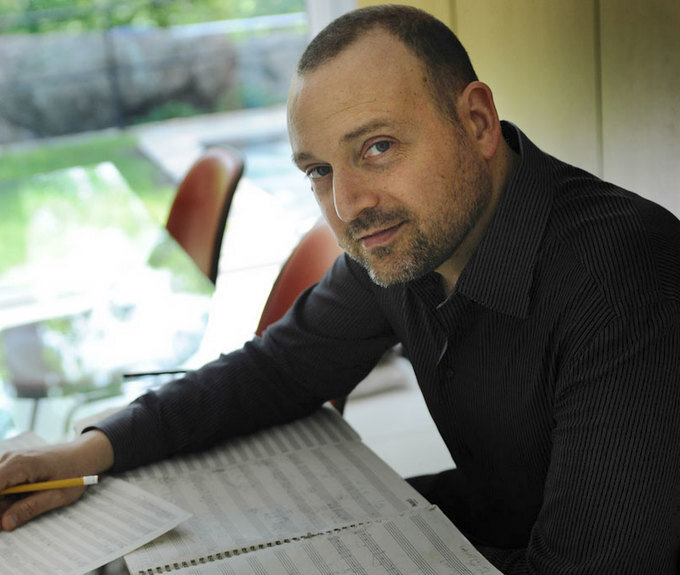

Derek Bermel (b. 1967)

Soul Garden

Derek Bermel's concert works have been deeply inspired by African-American music: jazz, blues, R&B and hip-hop have all influenced his writing. In Soul Garden he uses precisely notated glissandi and quarter-tones to capture the quality of gospel music. Substituting a quarter-tone for its corresponding chromatic counterpart connotes for Bermel an emotional, even sensual, inflection: the solo viola solo is made to resemble a burnished alto gospel singer; the cello a rumbling church baritone.

The work exploits the tension stemming from what Bermel calls the rub, the juxtaposition of the African pentatonic and European diatonic scales. Melodically and harmonically rooted at first, Soul Garden slowly moves away from its tonal center. By the viola cadenza, the glue holding the piece together is gesture, an element common to all of Bermel's works; yet each of these gestures can be traced back to the viola's opening motive. Bermel thus pays tribute to the Beethovenian ideal of generating the entire motivic content of a movement from an initial melodic seed. And in the cadenza, one hears a dialogue reminiscent of both call-and-response in gospel music and J.S. Bach's multidimensional solo writing; one example of how Soul Garden unearths common ground between disparate traditions.

Soul Garden was commissioned by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center for violist Paul Neubauer, who premiered it with cellist Fred Sherry and the Miami String Quartet on April 16 and 18, 2000 at Alice Tully Hall , New York City. It was recorded on CRI CD 895 by Neubauer, Sherry, and the Borromeo String Quartet, now available from New World Records.

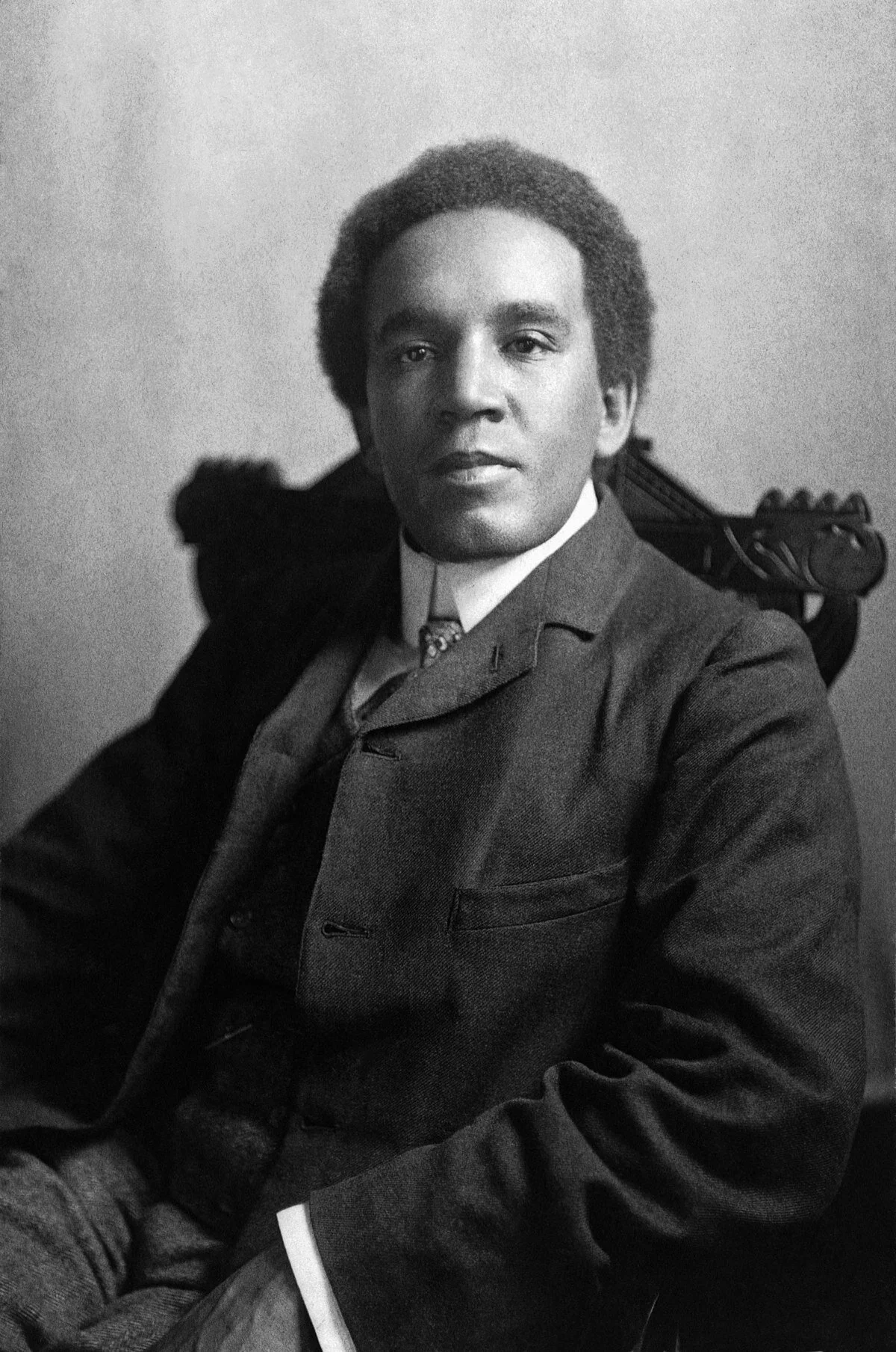

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912)

Clarinet Quintet in F-sharp Minor, Op. 10

by Scott Foglesong

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was raised in England and experienced an education similar to many English composers of the day: studies at the Royal College of Music under Charles Villiers Stanford (who taught just about everybody), professor at the Crystal Palace School of Music, and eventually some highly successful tours of the United States. He was of mixed-race birth, his father a prominent West African from Sierra Leone, his mother an Englishwoman. His death at age thirty-seven resulted in his posthumous legacy being given relatively short shrift compared to contemporaries such as Delius, Holst, Sullivan, and Elgar. His Hiawatha has remained in the repertory, as has a violin concerto, but that’s about it. So let’s all don our explorer togs: Coleridge-Taylor’s catalog is filled with jewels just waiting to be re-discovered.

Consider the Clarinet Quintet in F-sharp Minor, Op. 10, which originated with an offhand remark of Stanford’s to the effect that, after Brahms had written his autumnal Clarinet Quintet, nobody would be able to write another that wasn’t Brahmsian. Coleridge-Taylor took the bait (if that’s what it was) and produced a most decidedly non-Brahmsian clarinet quintet. (The Dvořák influence, on the other hand, is unmistakable.) With Coleridge-Taylor’s early death, this substantial and wholly effective piece fell into the shadows. A posthumous second act is very much in order.

Clara Schumann (1819–1896)

Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 20

by Scott Foglesong

The case of Clara Schumann poses one of the most tantalizing ‘what if’ scenarios in music. What if Clara Wieck had kowtowed to her overbearing but devoted father and had refrained from marrying Robert Schumann? Without a husband, eight children, and a household to care for, what might she have achieved? As it was, she achieved a great deal: superb pianist, muse for her husband, mentor to Johannes Brahms, influential teacher, and skilled composer.

For a while there it seemed as though posterity had forgotten about that last attribute, but wheels have a way of turning, and nowadays Clara Schumann the composer is getting her belated due.

She composed Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann several years after the family had relocated to Düsseldorf for Robert to take up his directorship of the orchestra. Clara hadn’t written a note in a good long while, but now she was ready to resume. On May 29, 1853 she wrote in her diary: “Today I … began … for the first time in years, to compose again; that is, I want to write variations on a theme of Robert’s out of Bunte Blätter, for his birthday: but I find it very difficult—the break has been too long.” Despite her reservations, no signs of struggle mar the finished product, expertly written for the piano (as one might expect) and offering the occasional ripe harmonic twist.

The Variations wound up amongst Clara’s last completed works. After Robert’s tragic death in 1856 she resumed her concert career, which left her with little time or energy for composition. That’s a pity. But what we have is decidedly fine, and thankfully, it’s receiving ever-increasing attention.

Banner image: Bonnie Rae Mills